My loneliest time in traveling is when everyone I love is sleeping at home and I am awake and by myself in an airport. I feel as if I have been forgotten, and if I wasn’t careful, I could end up on the wrong flight and find myself in Istanbul or some other faraway place when the doors opened on an unknown world.

I left my favorite dress in Budapest because I couldn’t imagine wearing it again. The memory of it swooshing around my ankles as I watched couples waltz in circles in a city park while the sun set over the Danube would make my heart ache for not being there again. But just as the old adage is correct—you can’t go home again—it is also true a lifetime happens once, and you can’t get it back to do a do-over.

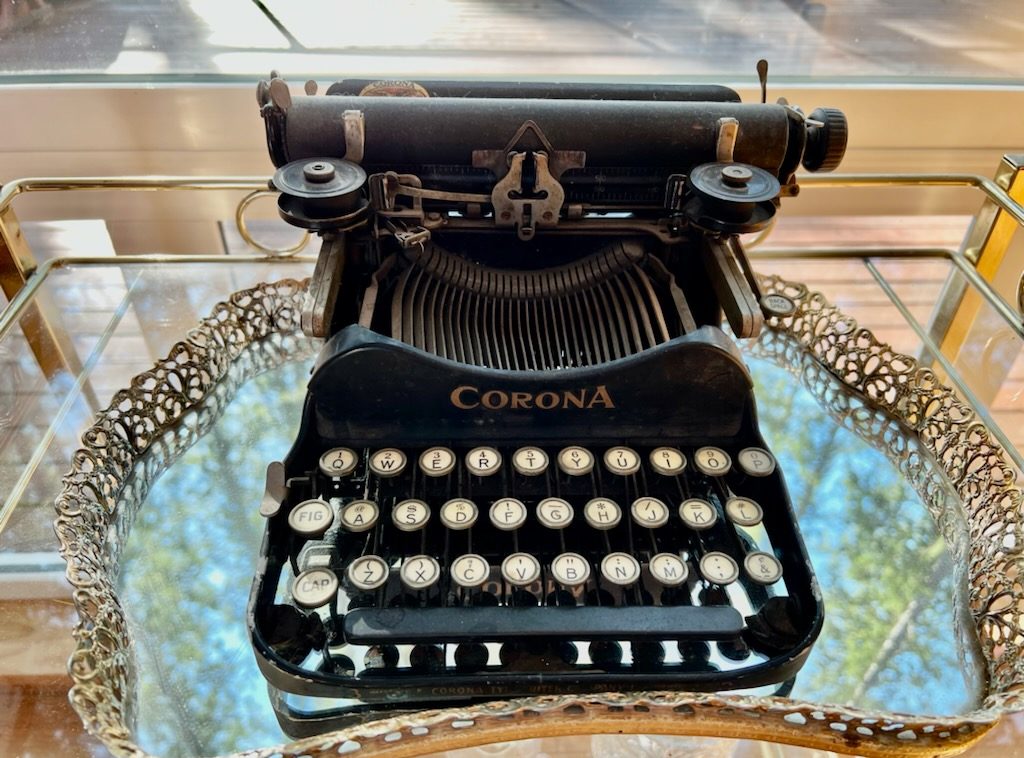

I have struggled with my writing while I have been on my trip. The heat was so oppressive, and our schedule had this start and stop shuffle to it like I couldn’t find the notes to the music I usually hear or feel the drumming in my chest that whispers, “Lesley, write.” I also couldn’t pin myself down. Who was I? I was no longer the mother responsible for the child, I was, at times, the travel companion whose skills tended more in the direction of asking for help instead of figuring it out through observation. SarahKate is latter if you didn’t know.

I think the dissonance happened because of the span of time that stretches, overlaps, and extends beyond in a parent child relationship. Think of it as a series of roads going in all directions. Where the roads intersect, your life joins with someone else’s, and you add a new name to your identity. I’ve always been a daughter. Throughout my life, I happened upon new roads and added the titles of sister, mother, wife, friend. Sometimes the roads are just crossings, other times they parallel one another, and even other times they merge for a long time, seamless, the two signposts becoming one before finally separating, because roads are by nature and design meant to be singular.

I’ve known SarahKate since before she was born. Before her birth I had a childhood, friends, lovers, an unhappy first marriage, and another child all tied together like a knitted wool hat that prepared me for her, my child. I knew from the time I was young that I would have a redhaired daughter. I can’t tell you how, but I knew it as firmly as I knew my middle name, my favorite book, or the qualities in a best friend. SarahKate has known me for as long as she has had memories. She was not born with the knowledge that she would someday have a mother with red hair. It just fell from around my face and brushed her newborn cheek from the moment she opened her eyes. I was 26, and it was the flaming, bright, startling red hair that she now sees in the mirror each day.

We had only a few scrapes on the trip—a incorrect train platform, a couple of misunderstood comments—but it was SarahKate who brought me to a place of acceptance that no one else has been able to on an issue I am facing as thick and impenetrable as the thorny thicket around Sleeping Beauty’s castle.

My parents helped me raise my kids after my divorce when my kids were tiny. I moved to another state, got a job working in a downtown office building, bought a house by myself, and traveled around the country delivering workshops. While all of that was happening to me, my parents were there for SarahKate and her brother—fixing dinner, lighting candles on the table, taking them to sports’ practices, tucking them in at night. They (except for the respite time they had in Arizona in the winter) did it all. It allowed me to work on my career which gave me the experience I needed to get my job in Olympia where I ultimately met Paul and knew that I was home for good.

SarahKate can tell me things about my parents, particularly my mother, that I didn’t know because I was gone so much during that time in her life. My mother brushed her hair, took her shopping, made cookies with her, watched television with her, walked the dog with her, and in general was always a buzzing presence that made everything else happen. My mother was the glue for them just as she was the glue for me and my brother when I was growing up.

Out of the deepest respect for my mother and her privacy, I won’t go into the particulars of the challenges she is facing as she grows older or how helpless I feel as her road diverges and leaves the one we shared. Many senior citizens experience breaking bones, becoming a widow, losing a pet, watching friends pass away, staring at a family vacation spot in the rearview mirror, and feeling a quiet despair about the days that seem endless—all markers on a road they alone know. It is her journey, her destination. I can only hope to wrap it in some semblance of dignity, so she doesn’t awaken one day to find the doors have opened at Istanbul or some other faraway place.

If do-overs could happen, I would find my mother’s Budapest dress for her to wear again. My father’s arms would be the ones around her impossibly tiny waist, his cheek would be against hers with his Aqua Velvet aftershave mixing with her Chanel No. 5 perfume as they swayed to Moon River, the song from the movie, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the song they owned together. Her brilliant, stunning red curls would swing in the light as they danced in circles.

Moon river, wider than a mile

I’m crossing you in style some day

Oh, dream maker, you heart breaker

Wherever you’re goin’, I’m going your way.

–Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer, 1961