Mojo. It’s when the stars align and passion carries you forward into the best you can do. In baseball it means seeing the seams on the ball as you swing the bat, but for a travel writer, even wardrobe malfunctions can be the exodus you need to push your writing to another level. I give you…my mojo without a top or a bottom.

A journalist turned cigar shop owner who counted Fidel Castro as one of his friends and a machete-wielding river tour guide were the Puerto Vallatra and Sayulita mojo-producing stories of my ten-day Mexican vacation.

We spent just one day in Puerto Vallarta, and that was more than enough. Hurricane Nora had gone through just a few days before our arrival, and it had decimated the city’s sanitation system. Brackish water covered the cobble-stoned streets up to the curbs and fountains of brown water bubbled up from the city’s manhole covers. The smell? It was like a dog park where too many dogs had a party and tried to hide the smell by peeing on it. The locals called it “aguas negras,” or literally “black waters” spilling into the ocean.

In spite of the smell and the creeping tide of sewage water, I had done my research, and I knew the exact six-block radius of shops between the Cathedral of Guadalupe and the Puerto Vallarta waterfront that would yield the best art galleries, women’s boutiques, and 2 for 1 margaritas. Shopping is my life; I’m truly gifted at it. To keep Paul hoping we were just around the corner from the aforementioned margaritas, I occasionally have to find him a store that he thinks he discovered. It gives him a point in the win column. The shop must embrace manliness. It doesn’t have to stock things for men per se; it just must make a man feel manly to cross the threshold. A shop sign jumped out from under the eaves of an old hacienda—La Casa del Habano. A cigar shop. Paul’s eyes lit up. He could tell his brothers he bought Cuban cigars. It was a win for both of us. He got the cool brother nod, and I got the coolest wife award.

After wiping our feet off thoroughly, we stepped into the store and were immediately wrapped in curls of cigar smoke.

“I’m going into the humidor,” Paul said with his hand on the doorknob of a glass-paneled door. Inside I saw rows and rows of cigar boxes containing wrinkled, brown stubs all snuggled up together in the dim light.

“I thought a humidor was a box with a see-through lid,” I said flatly.

“That is our home humidor. This is a man’s humidor,” Paul said softly as he eased the door shut behind him.

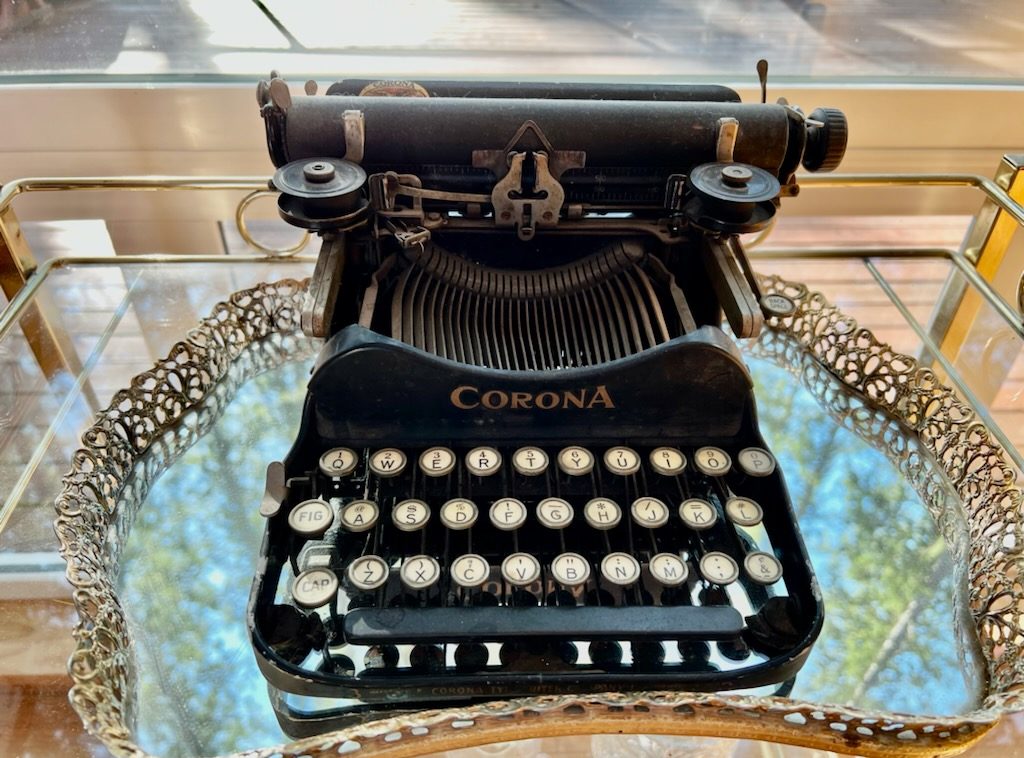

I looked around at the shop. This was a man’s world. Bottles of tequila, rum, and mezcal lined the window frames and bookshelves, and a brick staircase led down into a cool basement where cigar smoke was puffing from the corner.

“Welcome to my shop,” a voice said from the shadows. A light switched on, and a man who vaguely resembled Ernest Hemmingway was ensconced in the corner of a worn leather couch the color of Havana coffee. He was portly with a wrinkled shirt tight around his belly, a close-cropped silver beard and matching silver hair partly hidden under a Panama hat. “Drink?” He held out a bottle of mezcal.

“No thanks. I am waiting for my husband.” I looked around. There weren’t a lot of places to sit. I slid onto the leather couch at the other end from him.

“I smoke ten cigars a day. Five at home, five here in the shop.” He went silent and drew in a drag that filled his chest. “Smoke?”

“Not a day in my life,” I responded folding my hands over the purse in my lap.

“Too bad. You might like it. Especially had you started early.” There was an uncomfortable pause. “What do you do?” he asked.

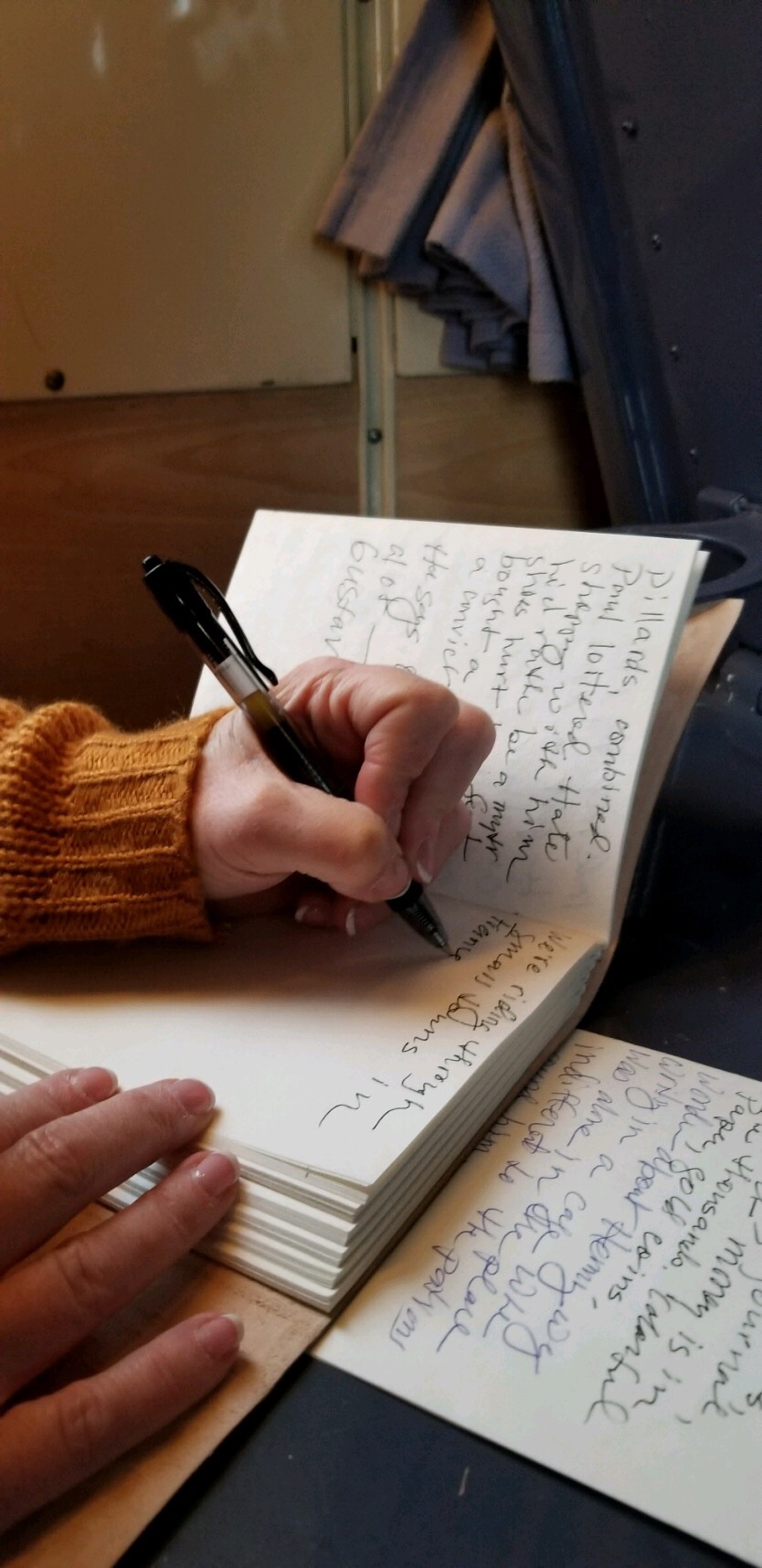

“I’m a writer.”

He leaned toward me and put an ash tray between us on the back of the couch. He tapped the ashes and then held the cigar out to me. “I’m a writer too.” I ignored the offering. “In fact, I was one of the only writers Fidel Castro allowed to interview him.” He blew smoke in the general direction of the ceiling. “Castro told me he’d had sexual intercourse 35,000 times in his life. Before breakfast, after lunch, and during siesta too,” he said breathlessly as he exhaled.

I felt sick to my stomach. “Well, I am headed to the humidor. Time for us to get going.” I trotted up the steps and pressed my hands and face on the outside of the cool glass of the door and used my fists to get Paul’s attention. I tipped my head towards the outside and motioned to my husband I was leaving.

While Mr. Fake Hemmingway wrapped up Paul’s purchases, I stood outside and smoothed my dress down in the stifling heat. Sweat dripped off the ends of my hair onto my skin and slid onto my neck, and I realized something didn’t feel right. I looked down and two buttons on the bosom of my dress had come undone. Not only was my chest open to the world, but my bra was a little tight and the ladies were propped and pushed like Marilyn Monroe’s.

I thought about telling Paul about Mr. Fake Hemmingway’s sleazy behavior towards me, but then I remembered there were three more stores to go, and one of them had multicolored leather sandals. People thought Marilyn Monroe was a ditz, but she managed to deftly handle an iconic playwright, a salacious president, and a major league baseball player with coyness and a pouty expression. I could take a page out of that gal’s playbook. I felt my mojo hum.

How do you tell a proud, macho tour guide that he dropped his machete in a small and accidental pocket? Paul shook his head in the negative as we stood behind Jorge, our tour guide for La Pila del Rey, a national heritage site for the Altavista petroglyphs, carvings made by the Tecoxquines, an Aztec tribe from the 16th century. His eyes gleaming in a wicked grin, Jorge had tossed the machete into the air over his shoulder. He thought it landed straight down into the big pocket, but instead it had tumbled it in the water bottle pocket leaving a two-inch slice in the worn fabric. I shook my fist at Paul silently and gave him the stink eye. I can’t believe a man’s delicate pride was more important than the very real chance I could be sliced by a bouncing two-foot-long rusty machete with bloody first aid tape for a handle.

Paul and I have hiked quite a bit together, just not in the last decade. With Jorge in front of me and Paul behind me, I didn’t have much of an exit strategy. I was stuck behind the machete, and all I could do was watch its movement. For the next two hours I trained my eyes on the machete like it was a bomb in an action movie.

Happily sharing his knowledge, Jorge led us on a scramble over boulders, a thigh-deep rain-swollen river crossing and sudden screeching halts to view over one hundred carvings. The machete swung wildly in every direction but gamely stayed in the small pocket. In the end I learned three things: one, the Texcoxquines deeply valued their gods and mind-altering substances; two, I was faster, quicker, and more resilient than I thought as I ducked and dodged the flipping and sliding machete (in fact, Jorge nicknamed me the little goat); and three, just when you let your guard down, trouble really happens. At the end of the river portion of the tour, Paul and I shot through a rock chute, down a waterfall, and into a deep pool. The force of water was so strong it stripped my bathing suit bottoms off and deposited them near a particularly large cluster of petroglyphs. For a moment I thought Jorge might pick them up with his machete and hand them to me, but thankfully he turned his back while I struggled to put them on in the churning water. You better believe my mojo was humming then.

For a travel writer, having your mojo in place is living life at its best. Losing my top and then my bottom may have been an uncomfortable way to arrive at that best of places, but Mr. Fake Hemmingway and Tour Guide Jorge, were the means to writing about this part of Mexico—where the sound of a tuba playing carries across the water, surfers linger off the coast waiting for the perfect wave, visible generations of dogs dash through town, never ending milk chocolate water crosses the path at the corner, walking through a cemetery is one way to get to the beach, and speed bumps come with tops or are topless. Tops and bottoms aside, I’d have called you crazy a week ago if you had told me Marilyn Monroe’s ghost would be the one to help me find my mojo.

“Too old to be getting married,”

“Too old to be getting married,”

So, that brings me back to the Night Market dance. In Chang Mai, there is a day market that sells indigo clothes, smocked pants, and all things elephant. The night market sells all of the same things, but it takes place at night where pastel lamps swing in the breeze, the flames of the street food surge with the cooking meat, Las Vegas-style Thai Lady Boys pose for pictures for 100BHT (three dollars), and people get up and sing karaoke. Here’s the deal—Night Market in Chang Mai is huge. I’m talking enough vendors to fill a football field. I’m talking a booming audio system for the karaoke.

So, that brings me back to the Night Market dance. In Chang Mai, there is a day market that sells indigo clothes, smocked pants, and all things elephant. The night market sells all of the same things, but it takes place at night where pastel lamps swing in the breeze, the flames of the street food surge with the cooking meat, Las Vegas-style Thai Lady Boys pose for pictures for 100BHT (three dollars), and people get up and sing karaoke. Here’s the deal—Night Market in Chang Mai is huge. I’m talking enough vendors to fill a football field. I’m talking a booming audio system for the karaoke.

“Are you sure?” The uber driver slowed the car to a stop. Silent warehouses lined the streets. There were no cars, no people, nothing except for a brightly-lit store front with a blinking, neon pizza sign. Inside the window I saw a man sweeping the floor and another man cleaning dishes in the sink.

“Are you sure?” The uber driver slowed the car to a stop. Silent warehouses lined the streets. There were no cars, no people, nothing except for a brightly-lit store front with a blinking, neon pizza sign. Inside the window I saw a man sweeping the floor and another man cleaning dishes in the sink.

“It’s 500 euros, Darling,” she coos. “A coat for life, a coat to remember Paris.” I feel myself weakening. If I average the cost of the coat across over my lifetime it begins to seem like a deal. The saleslady wanders away to allow Paul and I time to negotiate.

“It’s 500 euros, Darling,” she coos. “A coat for life, a coat to remember Paris.” I feel myself weakening. If I average the cost of the coat across over my lifetime it begins to seem like a deal. The saleslady wanders away to allow Paul and I time to negotiate.

The Louvre’s glittering pyramid looks like it has always been a part of the eight-century year old museum. Notre Dame’s Gothic spire and silent towers come to life when the bells toll. But, it is the moment you catch sight of her that make you swallow the lump in your throat and think to yourself, ‘It was worth the wait.’

The Louvre’s glittering pyramid looks like it has always been a part of the eight-century year old museum. Notre Dame’s Gothic spire and silent towers come to life when the bells toll. But, it is the moment you catch sight of her that make you swallow the lump in your throat and think to yourself, ‘It was worth the wait.’

We’re here. We’re in Paris. I’ve already overcome my initial fears: to find my luggage, secure a taxi, negotiate the language barrier, put in the correct codes to the building, and turn the key in the right lock of the right flat, and figure out how to use the toilet. I was afraid to face a bidet. I don’t quite get it. After 24 hours of flying, sitting, and eating food I normally wouldn’t eat, I need a glass of rose and a salad.

We’re here. We’re in Paris. I’ve already overcome my initial fears: to find my luggage, secure a taxi, negotiate the language barrier, put in the correct codes to the building, and turn the key in the right lock of the right flat, and figure out how to use the toilet. I was afraid to face a bidet. I don’t quite get it. After 24 hours of flying, sitting, and eating food I normally wouldn’t eat, I need a glass of rose and a salad.

He looked at them and didn’t say much. He stared at his phone and flicked a map on the screen whenever a commercial came on. I waited.

He looked at them and didn’t say much. He stared at his phone and flicked a map on the screen whenever a commercial came on. I waited. The first time we bought a boat we thought we would create lasting memories for our children. The second time we believed mooring a vessel in front of our house would magically make boating effortless.

The first time we bought a boat we thought we would create lasting memories for our children. The second time we believed mooring a vessel in front of our house would magically make boating effortless.

Finally, we paddled back to the beach. It took a while. We kept going in circles. In a few choice words, my husband informed me my strokes weren’t matching his. In silence, we dumped the rowboat into its hiding place.

Finally, we paddled back to the beach. It took a while. We kept going in circles. In a few choice words, my husband informed me my strokes weren’t matching his. In silence, we dumped the rowboat into its hiding place.

Paul and I stood alone on the side of the highway where we had been ejected by the wheezing, laboring bus. Los Achote was deserted. A few chickens clucked in the bushes and a faded Coca Cola sign stood in front of a building. It looked like any other small Mexican village. The roads were dusty and rutted. The houses were small and built creatively out of all types of building materials including wooden beams, concrete blocks, and rusted metal panels. The houses meandered along the street, some hidden in tall weeds others in plain view hugging the road.

Paul and I stood alone on the side of the highway where we had been ejected by the wheezing, laboring bus. Los Achote was deserted. A few chickens clucked in the bushes and a faded Coca Cola sign stood in front of a building. It looked like any other small Mexican village. The roads were dusty and rutted. The houses were small and built creatively out of all types of building materials including wooden beams, concrete blocks, and rusted metal panels. The houses meandered along the street, some hidden in tall weeds others in plain view hugging the road.

Paul and I dropped in an exhausted heap today at the beach. We grabbed a couple of chairs under a palapa and ordered a bucket of Pacifico beer from a beachfront restaurant called Irma’s. The waves were pounding a few yards away, but I was restless. I hate just laying on a chair. I was ready to walk. Someone had to save the chairs and keep track of our things, so I nominated Paul. Eyes closed, he nodded.

Paul and I dropped in an exhausted heap today at the beach. We grabbed a couple of chairs under a palapa and ordered a bucket of Pacifico beer from a beachfront restaurant called Irma’s. The waves were pounding a few yards away, but I was restless. I hate just laying on a chair. I was ready to walk. Someone had to save the chairs and keep track of our things, so I nominated Paul. Eyes closed, he nodded.

The quaint, raspberry pink-hued hotel, Paseo de Morro, is our very own Grand Marigold Hotel from the movie by the same name. It clutches the rocks on the side of the cliff hanging over Zihuatanejo Bay. There are 166 steps from our hotel down the hill into town. A few times we started the margaritas earlier than was advisable and the climb back to the hotel was demoralizing. Paul got cranky and told me to quit counting the stairs—he couldn’t bear it. I cackled and shouted the numbers.

The quaint, raspberry pink-hued hotel, Paseo de Morro, is our very own Grand Marigold Hotel from the movie by the same name. It clutches the rocks on the side of the cliff hanging over Zihuatanejo Bay. There are 166 steps from our hotel down the hill into town. A few times we started the margaritas earlier than was advisable and the climb back to the hotel was demoralizing. Paul got cranky and told me to quit counting the stairs—he couldn’t bear it. I cackled and shouted the numbers.

We are returning to Zihuatanejo in hopes that time has stood still in a few places and for some people, most notably our favorite restaurant, Bistro Del Mar, where four staff waited on us all at the same time (imagine four men pouring wine, pouring water, removing plates, and placing plates all simultaneously). We also look forward to the hotel staff at Paseo de Morro even if they did cluck like disapproving mother hens when we appeared at the top of the stairs tired, hot, and, let’s just say it—intoxicated.

We are returning to Zihuatanejo in hopes that time has stood still in a few places and for some people, most notably our favorite restaurant, Bistro Del Mar, where four staff waited on us all at the same time (imagine four men pouring wine, pouring water, removing plates, and placing plates all simultaneously). We also look forward to the hotel staff at Paseo de Morro even if they did cluck like disapproving mother hens when we appeared at the top of the stairs tired, hot, and, let’s just say it—intoxicated.